![]()

Games have usually been about killing. It’s the simplest objective and it’s the easiest thing to program. Be they Space Invaders or Inky, Blinky, Pinky, and Clyde, the annihilation of ones’ enemies was the initial goal of video games. It still stands as the primary gameplay feature in 95% of all games. The simplest iterations of this concept tested only the player’s endurance against increasing odds while more honed systems tested strategy, timing, and precision.

But had anyone ever stopped and considered the phrase, “live and let live?” In the early 1980’s, someone did—and thus the stealth genre emerged, rooted in the idea that direct confrontation may not always be the best way to defeat one’s enemies. In fact, it’s probably the worst.

The year was 1981 and Muse Software releases Castle Wolfenstein for the Apple II, later to be ported to DOS, the Atari 400/800, and the Commodore 64. You played an Allied soldier trapped in a Nazi fortress tasked to steal the ‘secret Nazi war plans.’ You had a gun, but bullets were extremely scarce and it was best to only kill when faced with no other choice.

At the time, the artificial intelligence in Castle Wolfenstein was revolutionary. Soldiers were alerted if they saw you walking around without a disguise. They heard sounds like gunfire and grenade explosions.

While pursued, normal soldiers could have been shaken off with relative ease, but once you started running into the SS, things got tricky. The SS had no qualms with chasing you from room to room.

If you managed to dispatch an enemy, his body could have been searched for ammunition, armor, and an extremely useful Nazi uniform that fooled the regular guards but not the SS. However, you didn’t have to kill an enemy to get his equipment. If you pulled out your gun to surprise an enemy, more often than not he’d put his hands up and you were able to frisk him for precious supplies. You then had a choice to kill him. The only other method of getting ammo was to use your lock pick to open chests, but didn’t offer enough to keep you alive.

The game succeeded in creating a sense of urgency by using digitized voices for the guards. However crude the sound quality was, the distinguishable German exclamations were enough to make you panic. And believe me—you’ll hear them quite often seeing as there are 60 rooms in the massive five story castle.

This style of gameplay carried over to the sequel, 1984’s Beyond Castle Wolfenstein, but with several changes. To increase the challenge, guards would occasionally ask the player for a pass (which varied by level), at which point you could either show your pass or offer a bribe. Naturally, if you didn’t have the right pass or you didn’t offer enough money, the guard would try to activate the alarm. The grenade was replaced by an incredibly useful dagger which allowed silent kills and the sound effects were greatly improved (in quantity and variety—not quality).

The stealth in the series ended here, though, as Muse Software went out of business in 1987. Id Software acquired the rights to Wolfenstein, which would lead to a landmark title in another genre.

Of course I’m talking about the seminal Wolfenstein 3D, considered by many to be the pioneer of the now ubiquitous FPS genre. The game had absolutely no stealth elements beyond shooting someone in the back. The game could just have easily been titled something else, but at the time the Wolfenstein franchise was a lucrative one.

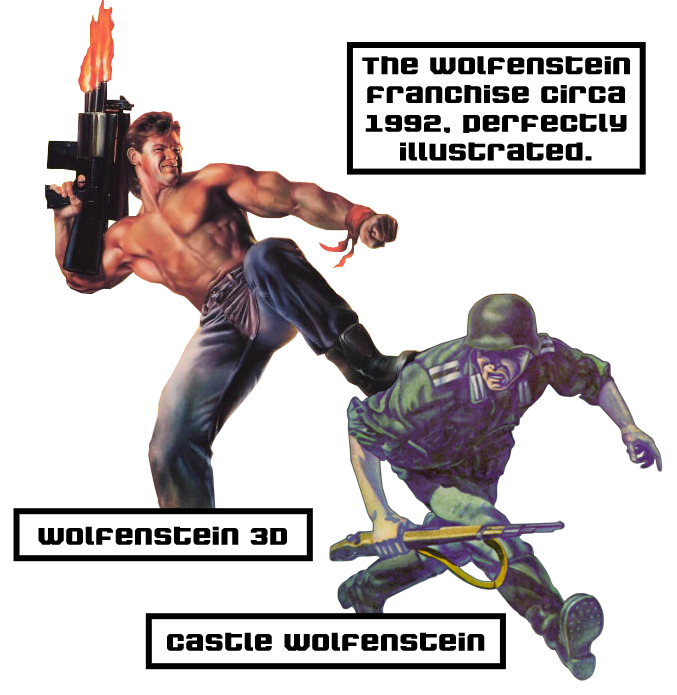

In memoriam of a trailblazer of the stealth genre, I’ll end this article with an image that so beautifully displays the shift of the focus of the Wolfenstein franchise. The macho man on the left, described by Elder-Geek.com Editor-in-Chief as “Patrick Swayze meets Contra,” is the guy you control in Wolfenstein 3D. The fellow on the right is the guy you control in Castle Wolfenstein. Think about it.