There’s been a lot of discussion about video game movies, and this article is just going to add to that, but I’m trying to approach it from a narrative standpoint. It’s widely agreed that video game movies aren’t all that good. They’re satisfactory at best, and insulting at worst depending on the demographic. For instance, gamers took greater offense to the liberties taken in the 2008 adaptation of Max Payne (the game came out in 2001) than non-gamers because of plot differences.

But consider other adaptations – of books and plays, for instance. Creative liberties are taken quite frequently with those types of properties, even when they’re better suited for more direct adaptations. Things are left out, things are added, yet the response is rarely as negative.

The reason for this attachment to the source material is undoubtedly connected to the unique element of video games that can never be replicated in film; interactivity, and it’s the key reason why video game movies ultimately disappoint most gamers. The best way to think of this is to consider one of your favorite games and imagine what it would be like if you just watched the game being played by another or only watched the cutscenes. Nobody likes the former, and the latter would leave many holes in the plot that are filled in during gameplay.

Also, consider the length–games that clock in at around 6 hours of playtime are considered short by many standards, yet that’s three times the average length of a feature film.

But it comes back to interactivity. Whereas books and plays are usually the result of one writer, and their film adaptations usually follow that formula (though multiple writers are not uncommon), video games have stories that are, in part, told and influenced by the player.

This leads me into narrative theory, and, first and foremost, character. In the simplest of terms, effective films are about a character that wants something very badly, has something in his way, and either gets what he wants or fails to do so. More often than not, the characters have flaws that make it harder for them to achieve their goals, and there’s a legitimate chance of the protagonist failing, meaning the audience hopes for one outcome and fears another.

In games, this is not the case. Failure is not an option, and flawed characters are few and far between. Games are made to be won, and most are designed with reward-based systems. This means that even the challenging segments of games result in achievements, improvements, and other “rewards.”

Think about games with greater focus on narrative – was there ever a doubt in your mind that Nathan Drake would succeed in all four Uncharted games? Or that Solid Snake would triumph in every single Metal Gear? Or that Max would exact his revenge in Max Payne?

The answer is no. Because then the games wouldn’t be complete. There’d be no way to win them, and game critics and gamers alike would universally pan them. The fact is, no obstacle in videogames is ever insurmountable, or even close. In films, there are obstacles that set the characters back in a big way (most transparently used in comedies, where everything goes to shit around three quarters of the way through – the best buds have a falling out, the team forfeits the competition, the girl misunderstands something and dumps the boy, etc.). Those obstacles are effective in films because we’re passive viewers. We’re watching someone else, and we’re hoping for him to overcome the obstacles, or fearing that he won’t.

In games, those kinds of setbacks are infuriating and a relic of the past when games were based on lives and points and quarters in arcades. Any game with something like that released in today’s gaming climate would be hated. Imagine losing half a dozen levels in an RPG, or losing half of your superpowers halfway through a game like inFamous.

Returning to actual characters – in films, characters are supposed to have arcs. They’re supposed to grow and mature in some way, and be different from how we saw them after the opening credits. In games, that’s less of an issue. In fact, in today’s sequel-saturated market, pressure is on game makers for Kratos to be the same undefeatable badass at the end of each God of War game. The same goes for characters like Dante from Devil May Cry, Ezio and his fellow assassins from the Assassin’s Creed series, even Guybrush Threepwood in Monkey Island. The games would cease to exist if, after one of his swashbuckling adventures, Guybrush matured into this more well-adjusted example of a man and was less of a bumbling buffoon. Mario needs to keep on being Mario. Link needs to keep on being Link. Samus needs to keep on being Samus. Even a game like Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, which defied convention by having its protagonist be an older, feebler version of what we’d seen before, failed to have an arc. Snake was older, yes, but as far as gameplay was concerned, he was just as deadly as he’d always been.

This brings me to flaws. Characters in films have them constantly, whether or not they are protagonists or antagonists. Video game characters? Not so much. The only one that immediately comes to mind is the Prince as he’s portrayed in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. He’s proud, but is later revealed to be frightened.

Then you have characters that are flawed less because of their character and more because of gameplay. Many characters in survival horror titles are perceived by the player as ‘weak’ because of stilted and stiff controls, or design decisions made by the developers (limited ammunition, overpowered enemies, etc.). That’s why the survival horror genre (the creepy kind like the Silent Hill or Siren seres) has lent itself to two comparatively good adaptations. Another aspect of survival horror games that translates extremely well to film is the atmosphere – the creepiness of the environments are essential to the aforementioned games, and it was relayed quite well in their respective adaptations.

Finally, you have blank characters in video games. Gordon Freeman from Half-Life, Link from The Legend of Zelda, and scores of mute RPG heroes. Obviously, there can be no successful adaptations of these games without a screenwriter somewhere creating a character of his own that shares the name of the protagonists we all control. And doing that is a recipe for disaster. A screenwriter writing a version of Gordon Freeman would only please a fraction of the gaming audience who happened to have the same vision of the character.

Other elements to consider are pacing and structure, which are of the utmost importance in storytelling. In films, the plot is carefully structured, typically, around three acts. Narrative theory established thousands of years ago by the likes of Aristotle are used as guidelines, to a point where, on a structural level, Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle is essentially identical to the Academy Award winning Winter’s Bone. Then there’s the whole Joseph Campbell approach (The Hero’s Journey), which follows another formula. Just read up on it and you’ll understand how prevalent it is.

In games, the pacing is radically different, because plot can be conveniently put on the back-burner during extended sequences of gameplay. Sandbox games have enough content where you can spend dozens of hours doing completely unrelated things to the point that you forget the main storyline. How can something like that be faithfully adapted in a film?

But in the end, I believe it comes down to interactivity. As gamers, we know more about the characters on screen than what’s being shown, and we can’t help but be disappointed when something is left out that we consider important. But it’s unavoidable. It’s a case of apples and oranges, with interactivity being the wildcard that can so radically change how a story is told in a game.

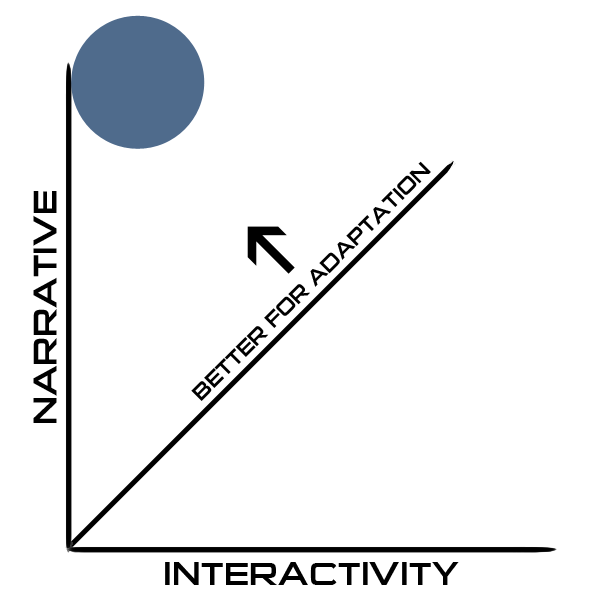

If I had to sum things up, I’d say that the more interactive the game, the less appropriate it is for adaptation; the greater attention to narrative, the better suited it is for adaptation. So that puts games like Indigo Prophecy and Heavy Rain as the games most ripe for adaptation – but I think we could all agree that to do so would be borderline redundant. (Although even with their limited interactivity, player choice results in numerous outcomes, and only one can be relayed in the film.) Allow me to end with this with a graph:

With the X axis being Interactivity, and the Y axis being Narrative, the top left corner of the graph is the area that holds the games that could yield potentially good adaptations. The bottom right, which would hold games like those in the Mario franchise…well…we all know how that turned out.